An important conference takes place at Birmingham City University Monday 7th July that explores the role of the professional media practitioner in British Higher Education.

I’m giving a paper asking the question asking whether the divide between practice and theory academics is the same as when I started teaching in universities in 1990.

I go further. I want to know if there has been any progress since the operation of the first British University diploma course in journalism that ran from 1919 to 1939.

I’m interested to know if anything has been done to bring down the walls and end a growing perception that media practice academics experience an apartheid in prospects, work loads, status, and promotion.

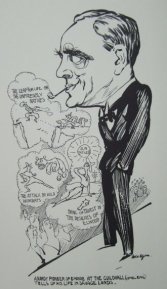

I have headed this article with a photograph of the Goldsmiths plumbing class from the 1920s because quite soon after starting my teaching of journalism and radio at the college I was being told by various sources outside the college that practice teachers in some parts of HE were nicknamed ‘plumbers’, ‘bricklayers’ and ‘button-pushers.’

My late friend and mentor Dr. Fred Hunter researched the history of the Diploma for Journalism course which was published as ‘Hacks and Dons’ shortly after his passing away in 2012.

It seems that the early years of the course were blighted by a refusal of the university to recognize that the teaching needed to be mainly practical.

There was a journalism committee advising the academics, but it took too long for the teaching of how to write editorials and reviews to be replaced with how to gather and write the news.

It was not until the arrival as ‘Director’ of a recent editor of the News Chronicle, Tom Clarke in 1935, that the students on the two year programme had at least two afternoons a week of real journalist reporting training and feedback.

There was an academic leader of the course Dr. George Harrison. He set about making the theory courses more relevant and interesting. So there was an emphasis on modern history blending with what we would now call ‘current affairs.’

The study of literature focused on recent and contemporary novelists, playwrights and poets. Political-economy was taught by a future leader of the Labour Party, Hugh Gaitskell.

Tom Clarke was supported on the staff by former student Joan Skipsey who made sure the students received immediate feedback and were assigned to a structured timetable of reporting the courts, civic meetings and London news events.

The students were taught in a ‘newsroom’ at King’s College on the Strand- a stone’s throw from the hub of Britain’s newspaper industry in Fleet Street. There were typewriters, and news feeds from the Press Association and Reuters.

In those final three years under Clarke’s direction, the course enjoyed its finest years. Why did it end? It would appear to be a combination of the Second World War and a failure by Hacks and Dons to bridge the practice-theory divide.

I think it’s telling that Clarke was not given the title of Professor. His background and social circumstances meant that he didn’t obtain a university degree. Being the editor of the News Chronicle, a quality broadsheet national newspaper and before that news editor of the Daily Mail, the country’s most successful newspaper, did not qualify him.

Neither did the fact that his teaching ethos, style and ability produced students who got jobs and were consistently praised by editors when out on internships.

British universities began offering postgraduate journalism courses from the 1970s. Undergraduate degrees were launched from the early 1990s. They were filling the vacuum of industry training schemes being shut down in recessions between booms and busts in media-land.

I came across an article Fred Hunter wrote for the Times Higher Educational Supplement published 31st January 1992 in which he’d interviewed Professor James Curran– the highly respected media theorist and historian in the department that has employed me for 24 years.

James said:

The absurd segregation between practice and theory will slowly melt down.

Fred wrote:

Curran believes we are coming to the end of the apartheid era, between media studies and journalism education, and are now in a process of reconstructing a multi-mix approach to journalism education.

Twenty two years later I can agree with James Curran that the melting down of the segregation has been slow.

I fear it has mainly been a one way process of osmosis rather than symbiosis. Media practitioner academics have had to become ‘hackademics.’

Professional media journalists or artists going into British Higher Education in their mature years after highly successful, award-winning and prestigious careers in their field usually have to start at the bottom.

Anybody entering is expected to train for and obtain a certificate in teaching and a PhD, preferably in the theoretical model while they are doing their full-time media practice academic job.

Mentoring and staff development support is uneven to say the least. Some universities pay the fees. Others do not.

What this means is that media professionals, often with families, are expected to do a full-time job which involves considerably more contact time and planning than their theory colleagues. They must also pay for and succeed in passing a Masters and then PhD programme, along with a PGCE.

If they missed out on university education, they have to do a first degree. They are expected to be supermen and superwomen, veritable Übermenschen.

It is also not altogether clear whether media and cultural studies are wholly relevant and useful to the thinking and intellectual disciplines that inform media practice.

Woe betide any media practitioner seeking academic qualifications in other academic disciplines.

The demand to become ‘real academics’ means that sacrifices have to be made. Instead of continuing to do the professional media work that gave media practitioners the authority of their expertise, they have to go back to school.

The research recognition culture in UK universities that has stubbornly refused to recognize and give equivalence to media practice output renders the knowledge, ability and value of many media practitioner academics as worthless.

And if the media practitioners turn out not to be good theory academics and UK HE suddenly starts to demand award-winning national and international media production outputs, they will find themselves drowning in a cold and brutal swell.

There’s another problem developing. Even when media hacks decide to become academics, they will find themselves in the slow lane of promotion.

What will this mean for undergraduate and postgraduate students paying £9,000 a year for media practice/theory courses?

I think there’s a real risk the students will not be getting the best teachers of journalism, film, animation or any other professional media skill. Being a great journalist and educator does not mean you are going to be a great PhD student, or even want to be.

And if the pay and promotion apartheid endures, why bother looking at Higher Education as a career? It will simply not be worth it.