At a time when British culture and society is going through a remarkable memorializing process about the ‘Great War’ of 1914-18, I have been impelled to elevate what I would regard the ‘forgotten history’ of Goldsmiths’ first Warden William Loring (1865-1915).

He not only laid the college’s key foundations for academic excellence and educational leadership, but was an incredibly courageous soldier who gave his life for his country at the age of 50 during the Gallipoli campaign. He was a decorated warrior having served valiantly in the second Boer War of 1899-1902. He commanded an officer cadet force at the College, and enthusiastically rejoined his Regiment, The Scottish Horse, on the outbreak of the First World War. He was grievously wounded in front line action in the ill-fated invasion of Turkey, died of his wounds on a hospital ship, and was buried at sea in the Aegean.

Loring was a Renaissance man for his age. In the Roman tradition of carrying the sword in one hand as a soldier defending nation and empire, he held the scrolls of learning in the other as a distinguished Cambridge scholar, archaeologist, barrister and educationalist.

Goldsmiths is beginning to explore its archives and it has recently published the pages of its December 1914 magazine the Goldsmithian, containing a fascinating letter sent by Loring following his re-enlistment one hundred years ago. Loring is certainly gung ho and encouraging students and staff to join up:

‘If this war continues, there will be opportunity of enlistment, with the full approval of the Board of Education, even for students who are committed to a course, perhaps a shortened course of pedagogic training. I venture to hope that many will avail themselves of the opportunity. And to those who do so I can wish nothing better than that the fortune of war may send them where their services will be drawn upon to the uttermost, and faith receive its keenest edge. This will, I believe, be good for the country, good for themselves, and good to the profession to which they belong.’

Loring was something at a loss as to what to say to his women staff and students except ‘I have addressed myself, inevitably, to the men rather than to the women,’ and sending them ‘cordial Christmas greetings.’

I have been at Goldsmiths for 24 years and have had no trouble working among Marxist-Leninists, anti-militarists, pacifists, and counter-imperialists. I believe Goldsmiths’ charm rests on the creativity of its avant-garde, non-conformist thinking and ability to agitate intellectually, politically and culturally. If William Loring had some extra-spiritual ability to think outside of his historical context, I am sure he would have been proud of the generation of academia that flourishes a century after he graced the corridors of what is now known as the Richard Hoggart main building.

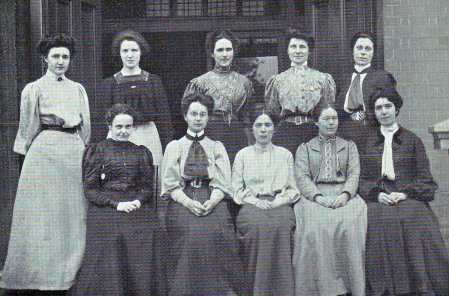

The Edwardian period was characterized by a cultural division of gender in terms of male and female students having separate corridors to walk up and down and, indeed, the staff official photographs symbolized the difference. All staff and students attended Morning Assembly where hymns were sung combined with Christian religious addresses and readings. All the students had to attend by register a mid-day meal with the Warden and senior colleagues wearing their academic gowns at a high table. The School of Art had to sit at a separate table that was positioned on a lower level! This was a time when women were campaigning for the right to vote in Parliamentary elections through the suffragist and suffragette movements.

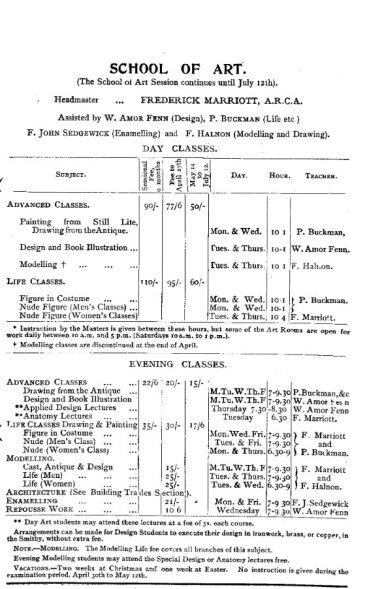

But in the midst of the social oppression of this period, Goldsmiths was pioneering artistic dimensions in teaching and learning. The first prospectus for Art is shown in a facsimile of the leaflet published at the time.

It should be noted men and women were not allowed to participate in the same Life Classes for Nude Figure and Modelling.

William Loring was the fourth son of the Reverend Edward Henry Loring, Vicar of Cobham and later Rector of Gillingham, Norfolk. Three of the four brothers would not survive active service during the First World War.

He had an elitist education though it can be presumed the privilege of his entry into the finest private schools was achieved by a combination of scholarship and clerical bursaries. He went to Fauconberg school in Beccles, Suffolk, then to Eton where he was a King’s Scholar and winner of the Newcastle Scholarship.

At King’s College Cambridge, he was a Scholar, winner of the Bell and Battle Scholarships, and the Chancellor’s Medal. He took First Class in both parts of the Classical Tripos becoming a college Fellow and was awarded the Craven Studentship of Archaeology.

It is reported that he had ‘a brilliant career’ as an archaeologist with several years’ work in the British School of Archaeology in Athens where he conducted excavations at Megalopolis.

He joined the civil service in 1894 as an examiner in the Education Department, was Private Secretary to Sir John Gorst and Sir William Anson, and Director of Education to the West Riding County Council prior to his appointment for ten years as the first Warden of Goldsmiths College.

He was also a qualified Barrister at Law of the Inner Temple and a member of 2 Hare Court Chambers. The first history of Goldsmiths College, ‘The Forge’ edited by Dorothy Dymond and published in 1955, records that:

His ten strenuous years as Warden included notable Presidency of the Training College Association. […] Innumerable tributes from many quarters were paid to his integrity, his leadership, his widespreading influence. His was a dedicated spirit and, in the words recorded in the Delegacy Minutes, “by the imprint of his character he gave a high tone to the College.” In an address to the Old Students in the Great Hall a month after Warden’s death Mr Raymont said: “As long as Goldsmiths College lasts, I think it may be said of him in this place that he, being dead, yet speaketh.”

A.E. Firth’s second history of Goldsmiths published in 1991 stated:

Loring and his colleagues intended right from the start to foster the growth of what might be called a ‘College Spirit’. Many of the students in the early years had little in the way of secondary education and had everything to learn about intellectual and cultural matters not touched on in their school classrooms. Some of them for example had hardly read a word of English Literature. So he and his colleagues took the lead in developing all kinds of non-academic corporate activities, a Literary and Debating Society, Musical and Dramatic Societies, Athletic Clubs and the like. He himself raised and commanded an Officers Training Corps. No doubt this corporate College spirit sometimes manifested itself in a sort of rugger club rowdiness. But the testimony of early generations of students does show that these efforts were remarkably successful. The way in which the Old Students’ Association flourished during its first six decades also shows how warmly its members felt about the College.

While it would appear that Loring fostered a classical and orthodox tradition in education, I suspect this encounter between middle-class, lower-middle class, and upper working class backgrounds would generate a creativity and dynamism that would later make the College unique in terms of media, arts and cultural expression. Seeds were being sown. For example, photography education was being pioneered through practice on the college green.

And this image from an annual sports day suggests the sexes operated a ritual of separation when most of the time they were in contact and experiencing the beginning of substantial social progress in terms of the move towards equality and representation.

Many decades later, the college green would host practice by the all women’s rugby union team. And if there were ever any kind of military cadet force in the future, it is likely to have more women in uniform than men.

William Loring was a volunteer for the Boer War joining the Imperial Yeomanry (Lothian) as a private in his 35th year in 1900.

He was later promoted to Corporal and then commissioned in the Scottish Horse Battalion.

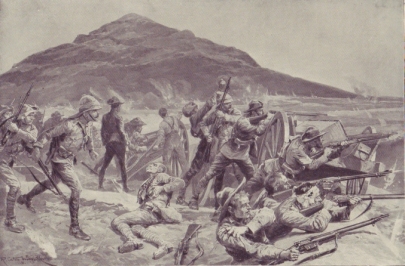

He joined the fighting during the conflict’s bloodiest and most violent period.

Over a hundred thousand white Boers had been detained in concentration camps and many died through starvation and disease.

The guerrilla war was often merciless.

The British gained the upper hand by learning to be mobile, understand the terrain, and match the Boer farmers for marksmanship, ruthlessness, and cunning.

Taking part in the conflict could have been seen as a single man seeking adventure in a dramatic Imperial story that dominated the media world of the time. The mounted infantry was a glamorous aspect of the British army’s operations that would be intensely reported on by newspaper and book publishers.

Loring was severely wounded and awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal, mentioned in despatches, and also received The Queen’s Medal with three clasps for taking part in action at Cape Colony, Orange Free State, Transvaal, in South Africa in 1901. He was promoted to captain 30th March 1903. This is the war diary account of the battle, written in military speak, in which he was recognized for distinguished conduct in the field and sustained his serious wounds:

[2526: 2539-2702] a farm in the South African Republic (Rustenburg district; North West), 25 km west of Rustenburg. On the afternoon of 29 September 1901, Col R.G. Kekewich’s

column halted on the farm near a drift across the Selons River and made preparations for the defence of the bivouac site.

The column comprised five companies of the 1st The Sherwood Foresters (Derbyshire) regiment, two squadrons of the Scottish Horse (a colonial unit), the 27th (Devonshire) company and 48th (North Somerset) company of the 7th Imperial Yeomanry and the 28th battery, Royal Field Artillery.

Commanded by Asst Cmdt-Gen J.H. de la Rey, a force left Dwarsspruit on the night of 29/30 September 1901 to attack the British bivouac.

The main assault led by Veg-Gen J.C.G. Kemp was from the bed of the Selons River on the west side of the bivouac. A patrol found by the 27th (Devonshire) company came across the advancing burghers and alerted the British troops.

De la Rey had also sent two groups to outflank the British camp and one was reported to be in the rear of the camp. With a group of cooks, orderlies and batmen, Maj C.N. Watts, The Sherwood Foresters (Derbyshire) regiment soon discovered there was little danger from this quarter and swung round to attack the Boer left supported by details from the The Border regiment, Scottish Horse and Imperial Yeomanry.

Wrapping up this flank, the Boer line was now enfiladed and the burghers began to retire. Boer losses were 11 killed, including Cmdt T.P. Boshoff, 35 wounded and ten burghers taken prisoner; the British lost 63 killed and mortally wounded and 151 wounded including Kekewich.

Pte W. Bees, Sherwood Foresters, was awarded the Victoria Cross for gallantry during this action. HMG IV pp.293-298 and 703 (map no.59); Times V pp.376385 (map facing p.382); Wulfsohn cap.21 (maps on pp.183 and 185).

A more journalistic account is to be found in volume 7 of the South Africa and the Transvaal War series:

At Dawn on 29th, he and Delarey (who had evidently followed Colonel Kekewich from the Valley of the Toelani) made a lunge at the British camp near Moedwill. From three sides they, some 1200 of them, turned a blizzard of lead on Colonel Kekewich’s force.

The Derbyshire Regiment, with 1 and a half companies, held the drift to left of the camp. The mounted troops (Imperial Yoemanry and Scottish Horse) extended round the right and front of the camp, and joined up with the Infantry outpost on the drift. Firing was heard at 4.40 A.M. on the north-west, and subsequently it was found that a patrol going out from the southerly piquet, furnished by the Devonshire Imperial Yoemanry, had been attached. Then closer and closer came the enemy upon the Yoemanry piquet. Every gallant fellow dropped. Soon the Boers were established to the east of the river and commenced an attack on another Imperial Yoemanry piquet. The officer in command fell, and nearly all his men around him. The enemy, ensconced in the broken and bushy ground near the bed of the river, continued the aggressive, while all in camp rushed to reinforce the piquets except a small party of the Derbyshire Regiment, which remained to guard ammunition, &c., the Boers having annihilated two piquets. The Boers now pushed up the river, outflanking the Derbyshire piquet holding the main drift, and, in spite of really superb resistance, occupied the position. For this reason : but one man of the gallant number remained whole! The camp now was flooded with bullets, and all ranks under various officers made for the open, while the guns strove to keep the enemy, indistinguishable from British in the dusk of the morning, at a distance. Captain Watson, Adjutant Scottish Horse, who was mortally wounded, announced the arrival towards the east of the enemy, whereupon Major Watts with a strong body of the Derbyshire Regiment moved out to confront them, while Major Browne (Border Regiment) with a number of men- servants, cooks, orderlies, and any one who came to hand- prepared with fixed bayonets to charge the enemy in the bushes. The Boers had given up the east, however, and continued to file from the north till the Imperial Yeomanry and Scottish Horse, under Captains Rattray, Dick Cunyngham, and Mackenzie, joined in the general advance and threatened to outflank them; then, seeing their danger, they fled to their horses and galloped madly to the north, under fire of the British guns. Colonel Duff, with two squadrons, had been prepared for pursuit, but owing to the heavy losses sustained, especially among the horses, the project was impossible.

The fierce, determined, carefully-planned attack lasted two hours, and the success of the repulse was mainly due to the amazing gallantry of all ranks, especially of the 1st Battalion Derbyshire Regiment.

You will notice that the language used here is as if the writer were describing a sporting contest. The reality of war had in fact left huge casualties of dead, dying and maimed on the battle-field.

William Loring’s First World War Service

It was inevitable that William Loring would answer the call to arms in 1914 with the outbreak of the First World War. As The Forge reports, the patriotic and military spirit, cultivated by Loring’s leadership was followed by students and staff:

Nearly 100 students in the Training Department enlisted before completing their College courses. About 600 Old ‘Smiths were known to be on active service. Decorations included 1 D.S.O., 11 Military Crosses, 13 Military Medals, 5 D.C.M.s, 2 Croix de Guerre, and 10 Mentioned in Despatches. Two members of the teaching staff (Captain W. Loring and Lieut. W. T. Young), one member of the office staff, 92 Training Department students and 11 from the Evening and Art Department were killed.

‘A brave soldier and a nature’s gentleman, who had not one thought except for his country.’

It seems rather remarkable that the now married and family man, William Loring, should return to front line duties at the age of 50 at a time when life expectancy, even for the middle classes, was much less than it is now.

He rejoined the Scottish Horse in August 1914 and served on home defence in various parts of Britain before leaving for the Mediterranean in August 1915. He and his regiment landed at Gallipoli on 1st September.

By October 21st he was critically wounded in action. He died three days later on the hospital ship, Devanha, taking him to Egypt.

He was buried in the Aegean Sea. Such a ceremony would have taken place on deck with the body placed on a slanting board, covered with a union jack. The burial service would be read by the Padre or Captain of the ship with troops and medical staff attending.

This remarkable account of his bravery and gallantry was written by Brigadier-General Lord Tullibardine, commanding the Scottish Horse, in a letter to Loring’s uncle- General Sir John Watson- a Victoria Cross holder:

‘I met your son the other day at Suvla, and he asked me to let you know about Capt. Loring. Loring died the gentleman and the soldier that he was. I had just taken over some bad lines 600 yards from the enemy, waterlogged, enfiladed, commanded, sniped.

I determined to shove on to the crest line between us, and, if possible, rush it in one night.

The key I considered to be White House in the centre. The Turks used to crawl up in the bush, and our casualties were frequent. Officer Commanding 2nd Scottish Horse was ordered to send out a squadron of the 3rd Scottish Horse to form a point d’appui for the leading squadron in case of trouble.

Also, they were to dig a communication trench back to our lines. Col McBarnet selected Loring as his most reliable squadron leader. All went well.

Within half an hour of starting a telephone came to say that Loring had occupied the house. Later came the message that the leading party had retired less Loring and three or four wounded men under heavy fire to A.

I immediately telephoned and told Col. McBarnet to reoccupy White House without delay, and sent Major Souter, I.A., a regular officer, out to take charge of the operation, which completely succeeded.

The house was occupied, and 100 yards of trench dug and consolidated before morning with very few casualties, despite a good deal of opposition.

The result is that by advancing at much the same time my two flanks, we have been able to push forward our line on an average 300 yards closer to the Turks, on better ground in every sense, for a distance of 950 yards, and shortening the line 250 yards as well…Above is to a great extent due to Loring’s grit at first.

It appears he went out, and all was well, and he telephoned back to that effect.

He then went back and started the men digging. By this time a heavy fire was opened on the party by snipers from all around.

Loring behaved, as always, with coolness and gallantry, but soon was himself severely wounded- thigh smashed.

While fully conscious he continued to take command, but as he got weaker and the fire increased, he ordered his subaltern, 2nd Lieut. Rodger, quite a lad, to leave him to the Turks, not to lose anymore men on him or the operation.

Rodger then ordered the men back, and they retired unwillingly, as they were devoted to Loring, and did not like going back and leaving him.

Rodger himself, having got the men under cover, gallantly but wrongly went back to Loring, and stuck to him and the wounded men through heavy fire; but as he had left his men and did not realize that he ought to have assumed command, and not taken orders from a wounded officer in a state of collapse, I did not mention him for ‘doing well.’

Poor Loring’s last sensible thoughts were for his men, and never mind him.

He refused to be carried off the field.

However, as I have told you, all ended well, and the operation which he had started and planned panned out just as we’d all hoped.

He made his dispositions well and skillfully, and the mere fact that he himself was still out and had not retired and was not a prisoner, was the kind of flash to me to send back his men at the double without a second’s pause or hesitation, and right willingly they went.

I did not see Loring again, as I had to personally superintend the consolidation of our line.

But all told me how fine he was in hospital.

I think he knew, but he never showed it.

The doctor told me when he went on the ship that the chances were not good, but he might do it.

We have lost an old and good friend, a brave soldier and a nature’s gentleman, who had not one thought except for his country, and whose greatest pride was to think that he had been permitted to serve it on service. I think he died as he would have had it.

Young Rodger since then has again behaved with conspicuous gallantry. I have recommended him for the military Cross, not only for the new act, but for the Loring incident as well.

William Loring’s widow, Mary, had no body to bury and mourn. She received the news of her husband’s death by telegram to Allerton House, Grote’s Buildings, Blackheath. Their son, John Henry, was 9 years old at the time.

Loring was posthumously mentioned in Despatches by General Sir Charles Monro in the London Gazette of 11th July 1916 for ‘gallant and distinguished service in the field.’ His World War 1 medal card sets out very briefly the official account of his war service and the medals his widow received.

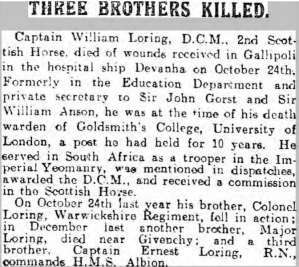

The tragedy of William Loring’s death had much wider implications and was felt and reported throughout the country. He was the third of four sons who had been killed by October 1915 as these reports in regional newspapers so poignantly indicate.

The Liverpool Daily Post reported on 3rd November 1915:

Cheshire Family’s Losses.

News has been received by Mr. John Loring, of Doddington Cottage, Nantwich, of the death of his brother, Captain William Loring, of the Scottish Horse, who has succumbed to wounds received in Gallipoli. Two other brothers of Mr. Loring’s, one of whom was Lieut.Colonel Loring, of the Warwickshires, who was killed when gloriously leading his regiment into action in France, have fallen. Mr. Loring has also lost a son and two cousins, whilst his eldest son, Captain E.J. Loring, has been twice wounded.

How William Loring is remembered 100 years later

The past is certainly another country. The values and world of 1914 and 1915 seem so alien and different to the world of Goldsmiths College in the present. The quaint mixture of early motor-car and horse-drawn traffic familiar to Loring before he and so many other students and staff left for the Great War have been replaced by the pollution of the South Circular, the noise of juggernauts and emergency vehicle sirens. Though the architecture and shop front usage of the New Cross Road are not that different.

I believe it may be much harder for the radical and non-militaristic community of Goldsmiths in the present age to appreciate the patriotic and martial spirit of the college under Loring’s Wardenship. There is also the fascinating irony that for many decades the college has developed next to a part of London’s vibrant Turkish community.

To think that Loring and so many Goldsmiths’ alumni fought for Great Britain and Empire against the ancestors of our local Turkish community when Istanbul had been capital of the Ottoman Empire.

For myself, as the son of gallant infantry officer, and a family with military service and sacrifice in the First and Second World War, I can certainly engage with the heritage of Loring’s legacy and military career.

And it is my intention through this article to give the noble first Warden respect and recognition in the new medium of online communication. I hope this background can help the 21st century generations of students from all parts of the UK and abroad seen arriving below to enquire about their accommodation at Loring Hall to connect with a man of grit, a true gentleman, and servant to education and public service.

Different perspectives of the bust of William Loring, Imperial War Museum images of the Gallipoli Campaign and the sound of ‘The Red, White and Blue’ sung and performed by the King’s Military Band and its chorus, released by Regal in October 1914.

William Loring, first Warden of Goldsmiths College- an audio slideshow. from TimCrook on Vimeo.

New Developments in the research into the history of William Loring

William Loring’s grandson, David, has been developing a very significant web-resource publishing and transcribing hitherto private letters and documentation surrounding the First Warden’s life, service and death at Gallipoli in 1915.

It is the generous intention of Loring’s descendants to donate these documents to Goldsmiths Special Collections and Archives so that they are permanently preserved in the College library.

The website has scanned the original letters and revealed very poignant and moving accounts of William Loring’s courage and leadership on the battlefield as well as the very last letter he wrote to his wife Theo on the day of the amputation of his leg and death from gangrene.

There is also correspondence from the Hospital Ship’s chaplain and Nurse Sister who witnessed his last moments.

A remarkable account of what happened to Captain Loring when he was wounded and how he insisted on soldiers being cared for before him was sent to his widow, Theo, from Private W. Coulter.

Sources and References.

Creswicke, Louis, South Africa and the Transvaal War: Lord Kitchener and The Guerilla War, Volume 7, London: Caxton Publishing, (1902).

Dymond, Dorothy ed., The Forge: The History of Goldsmiths’ College 1905-1955, London: Methen & Co. Ltd., (1955).

Firth, A.E., Goldsmiths’ College: A Centenary Account, London: The Athlone Press, (1991).

The Archives of Goldsmiths, University of London. Special thanks to Alice Measom, Archivist, Library.

The National Archives, WO128. Imperial Yeomanry, Soldiers’ Documents, South African War.

The National Archives, WO372/12, William Loring, Captain, Scottish Horse.

The National Archives, WO128/0027-141, Loring, William.

The National Archives, WO 95/4293, War Diaries of The Scottish Horse, Gallipoli, Dardenelles, 1915.

Ruvigny et Raineval, Melville Henry Massue, marquis de, De Ruvigny’s Roll of Honour 1914-1918 in 5 volumes, Uckfield, England: Naval & Military (2003, 1922) pages 205-6.

The Hull Daily Mail 3rd November 1915.

The Liverpool Daily Post 3rd November 1915.

The Dundee Evening Telegraph 4th November 1915.

Visit the other excellent resources on Goldsmiths and the Great War

Alex Watson argues the German motivation behind the First World War was love, not hate

Telling the stories behind World War One

Goldsmiths World War One Creative Awards

Commemorated at other sites and war memorials.

An excellent history of my Grandfather, which much more information than I can muster! Such as I have can be found here https://williamloring.wordpress.com/ including an image of the telegram on the occasion of William’s death that is referred to above.

A subsequent letter on the day of William’s death has come to light which indicates that his final letter was dictated to a Major R.B. Morton who was in the bed beside him. Moreton’s letter to Theo is now on my website. https://williamloring.wordpress.com/2015/10/11/letter-from-rb-morton-to-mrs-loring-24-october-1915/